A New Measure of Well-Being From a Happy Little Kingdom - New York Times

The New York Times

October 4, 2005

A New Measure of Well-Being From a Happy Little Kingdom

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

What is happiness? In the United States and in many other industrialized countries, it is often equated with money.

Economists measure consumer confidence on the assumption that the resulting figure says something about progress and public welfare. The gross domestic product, or G.D.P., is routinely used as shorthand for the well-being of a nation.

But the small Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan has been trying out a different idea.

In 1972, concerned about the problems afflicting other developing countries that focused only on economic growth, Bhutan's newly crowned leader, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, decided to make his nation's priority not its G.D.P. but its G.N.H., or gross national happiness.

Bhutan, the king said, needed to ensure that prosperity was shared across society and that it was balanced against preserving cultural traditions, protecting the environment and maintaining a responsive government. The king, now 49, has been instituting policies aimed at accomplishing these goals.

Now Bhutan's example, while still a work in progress, is serving as a catalyst for far broader discussions of national well-being.

Around the world, a growing number of economists, social scientists, corporate leaders and bureaucrats are trying to develop measurements that take into account not just the flow of money but also access to health care, free time with family, conservation of natural resources and other noneconomic factors.

The goal, according to many involved in this effort, is in part to return to a richer definition of the word happiness, more like what the signers of the Declaration of Independence had in mind when they included "the pursuit of happiness" as an inalienable right equal to liberty and life itself.

The founding fathers, said John Ralston Saul, a Canadian political philosopher, defined happiness as a balance of individual and community interests. "The Enlightenment theory of happiness was an expression of public good or the public welfare, of the contentment of the people," Mr. Saul said. And, he added, this could not be further from "the 20th-century idea that you should smile because you're at Disneyland."

Mr. Saul was one of about 400 people from more than a dozen countries who gathered recently to consider new ways to define and assess prosperity.

The meeting, held at St. Francis Xavier University in northern Nova Scotia, was a mix of soft ideals and hard-nosed number crunching. Many participants insisted that the focus on commerce and consumption that dominated the 20th century need not be the norm in the 21st century.

Among the attendees were three dozen representatives from Bhutan - teachers, monks, government officials and others - who came to promote what the Switzerland-size country has learned about building a fulfilled, contented society.

While household incomes in Bhutan remain among the world's lowest, life expectancy increased by 19 years from 1984 to 1998, jumping to 66 years. The country, which is preparing to shift to a constitution and an elected government, requires that at least 60 percent of its lands remain forested, welcomes a limited stream of wealthy tourists and exports hydropower to India.

"We have to think of human well-being in broader terms," said Lyonpo Jigmi Thinley, Bhutan's home minister and ex-prime minister. "Material well-being is only one component. That doesn't ensure that you're at peace with your environment and in harmony with each other."

It is a concept grounded in Buddhist doctrine, and even a decade ago it might have been dismissed by most economists and international policy experts as naïve idealism.

Indeed, America's brief flirtation with a similar concept, encapsulated in E. F. Schumacher's 1973 bestseller "Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered," ended abruptly with the huge and continuing burst of consumer-driven economic growth that exploded first in industrialized countries and has been spreading in fast-growing developing countries like China.

Yet many experts say it was this very explosion of affluence that eventually led social scientists to realize that economic growth is not always synonymous with progress.

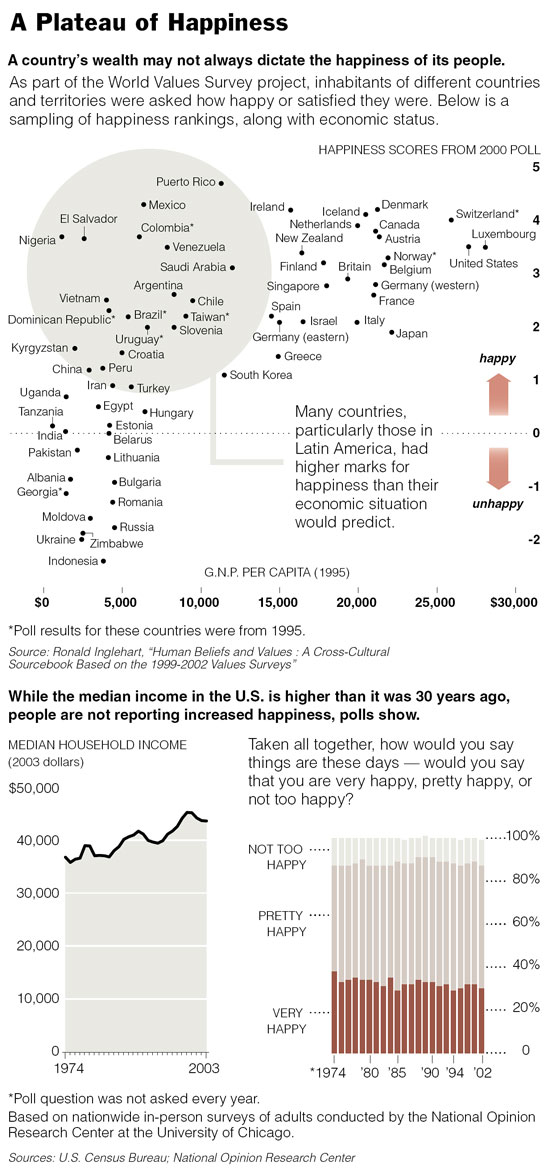

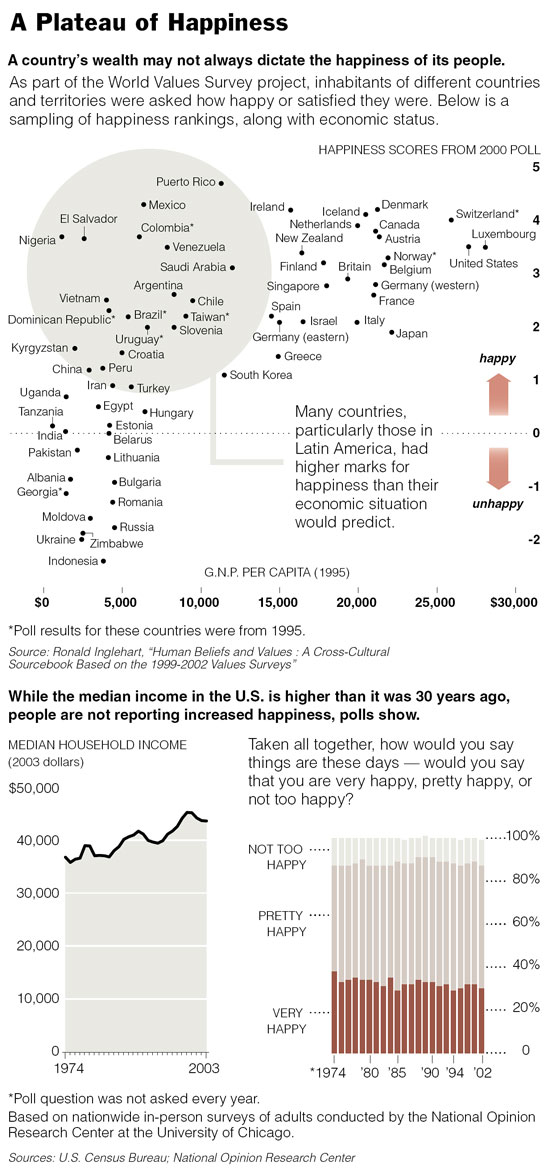

In the early stages of a climb out of poverty, for a household or a country, incomes and contentment grow in lockstep. But various studies show that beyond certain thresholds, roughly as annual per capita income passes $10,000 or $20,000, happiness does not keep up.

And some countries, studies found, were happier than they should be. In the World Values Survey, a project under way since 1995, Ronald Inglehart, a political scientist at the University of Michigan, found that Latin American countries, for example, registered far more subjective happiness than their economic status would suggest.

In contrast, countries that had experienced communist rule were unhappier than noncommunist countries with similar household incomes - even long after communism had collapsed.

"Some types of societies clearly do a much better job of enhancing their people's sense of happiness and well-being than other ones even apart from the somewhat obvious fact that it's better to be rich than to be poor," Dr. Inglehart said.

Even more striking, beyond a certain threshold of wealth people appear to redefine happiness, studies suggest, focusing on their relative position in society instead of their material status.

Nothing defines this shift better than a 1998 survey of 257 students, faculty and staff members at the Harvard School of Public Health.

In the study, the researchers, Sara J. Solnick and David Hemenway, gave the subjects a choice of earning $50,000 a year in a world where the average salary was $25,000 or $100,000 a year where the average was $200,000.

About 50 percent of the participants, the researchers found, chose the first option, preferring to be half as prosperous but richer than their neighbors.

Such findings have contributed to the new effort to broaden the way countries and individuals gauge the quality of life - the subject of the Nova Scotia conference.

But researchers have been hard pressed to develop measuring techniques that can capture this broader concept of well-being.

One approach is to study how individuals perceive the daily flow of their lives, having them keep diary-like charts reflecting how various activities, from paying bills to playing softball, make them feel.

A research team at Princeton is working with the Bureau of Labor Statistics to incorporate this kind of charting into its new "time use" survey, which began last year and is given to 4,000 Americans each month.

"The idea is to start with life as we experience it and then try to understand what helps people feel fulfilled and create conditions that generate that," said Dr. Alan B. Krueger, a Princeton economist working on the survey.

For example, he said, subjecting students to more testing in order to make them more competitive may equip them to succeed in the American quest for ever more income. But that benefit would have to be balanced against the problems that come with the increased stress imposed by additional testing.

"We should not be hoping to construct a utopia," Professor Krueger said. "What we should be talking about is piecemeal movement in the direction of things that make for a better life."

Another strategy is to track trends that can affect a community's well-being by mining existing statistics from censuses, surveys and government agencies that track health, the environment, the economy and other societal barometers.

The resulting scores can be charted in parallel to see how various indicators either complement or impede each other.

In March, Britain said it would begin developing such an "index of well-being," taking into account not only income but mental illness, civility, access to parks and crime rates.

In June, British officials released their first effort along those lines, a summary of "sustainable development indicators" intended to be a snapshot of social and environmental indicators like crime, traffic, pollution and recycling levels.

"What we do in one area of our lives can have an impact on many others, so joined-up thinking and action across central and local government is crucial," said Elliot Morley, Britain's environment minister.

In Canada, Hans Messinger, the director of industry measures and analysis for Statistics Canada, has been working informally with about 20 other economists and social scientists to develop that country's first national index of well-being.

Mr. Messinger is the person who, every month, takes the pulse of his country's economy, sifting streams of data about cash flow to generate the figure called gross domestic product. But for nearly a decade, he has been searching for a better way of measuring the quality of life.

"A sound economy is not an end to itself, but should serve a purpose, to improve society," Mr. Messinger said.

The new well-being index, Mr. Messinger said, will never replace the G.D.P. For one thing, economic activity, affected by weather, labor strikes and other factors, changes far more rapidly than other indicators of happiness.

But understanding what fosters well-being, he said, can help policy makers decide how to shape legislation or regulations.

Later this year, the Canadian group plans to release a first attempt at an index - an assessment of community health, living standards and people's division of time among work, family, voluntarism and other activities. Over the next several years, the team plans to integrate those findings with measurements of education, environmental quality, "community vitality" and the responsiveness of government. Similar initiatives are under way in Australia and New Zealand.

Ronald Colman, a political scientist and the research director for Canada's well-being index, said one challenge was to decide how much weight to give different indicators.

For example, Dr. Colman said, the amount of time devoted to volunteer activities in Canada has dropped more than 12 percent in the last decade.

"That's a real decline in community well-being, but that loss counts for nothing in our current measure of progress," he said.

But shifts in volunteer activity also cannot be easily assessed against cash-based activities, he said.

"Money has nothing to do with why volunteers do what they do," Dr. Colman said. "So how, in a way that's transparent and methodologically decent, do you come up with composite numbers that are meaningful?"

In the end, Canada's index could eventually take the form of a report card rather than a single G.D.P.-like number.

In the United States there have been a few experiments, like the Princeton plan to add a happiness component to labor surveys. But the focus remains on economics. The Census Bureau, for instance, still concentrates on collecting information about people's financial circumstances and possessions, not their perceptions or feelings, said Kurt J. Bauman, a demographer there.

But he added that there was growing interest in moving away from simply tracking indicators of poverty, for example, to looking more comprehensively at social conditions.

"Measuring whether poverty is going up or down is different than measuring changes in the ability of a family to feed itself," he said. "There definitely is a growing perception out there that if you focus too narrowly, you're missing a lot of the picture."

That shift was evident at the conference on Bhutan, organized by Dr. Colman, who is from Nova Scotia. Participants focused on an array of approaches to the happiness puzzle, from practical to radical.

John de Graaf, a Seattle filmmaker and campaigner trying to cut the amount of time people devote to work, wore a T-shirt that said, "Medieval peasants worked less than you do."

In an open discussion, Marc van Bogaert from Belgium described his path to happiness: "I want to live in a world without money."

Al Chaddock, a painter from Nova Scotia, immediately offered a suggestion: "Become an artist."

Other attendees insisted that old-fashioned capitalism could persist even with a shift to goals broader than just making money.

Ray C. Anderson, the founder of Interface Inc., an Atlanta-based carpet company with nearly $1 billion in annual sales, described his company's 11-year-old program to cut pollution and switch to renewable materials.

Mr. Anderson said he was "a radical industrialist, but as competitive as anyone you know and as profit-minded."

Some experts who attended the weeklong conference questioned whether national well-being could really be defined. Just the act of trying to quantify happiness could threaten it, said Frank Bracho, a Venezuelan economist and former ambassador to India. After all, he said, "The most important things in life are not prone to measurement - like love."

But Mr. Messinger argued that the weaknesses of the established model, dominated by economics, demanded the effort.

Other economists pointed out that happiness itself can be illusory.

"Even in a very miserable condition you can be very happy if you are grateful for small mercies," said Siddiqur Osmani, a professor of applied economics from the University of Ulster in Ireland. "If someone is starving and hungry and given two scraps of food a day, he can be very happy."

Bhutanese officials at the meeting described a variety of initiatives aimed at creating the conditions that are most likely to improve the quality of life in the most equitable way.

Bhutan, which had no public education system in 1960, now has schools at all levels around the country and rotates teachers from urban to rural regions to be sure there is equal access to the best teachers, officials said.

Another goal, they said, is to sustain traditions while advancing. People entering hospitals with nonacute health problems can choose Western or traditional medicine.

The more that various effects of a policy are considered, and not simply the economic return, the more likely a country is to achieve a good balance, said Sangay Wangchuk, the head of Bhutan's national parks agency, citing agricultural policies as an example.

Bhutan's effort, in part, is aimed at avoiding the pattern seen in the study at Harvard, in which relative wealth becomes more important than the quality of life.

"The goal of life should not be limited to production, consumption, more production and more consumption," said Thakur S. Powdyel, a senior official in the Bhutanese Ministry of Education. "There is no necessary relationship between the level of possession and the level of well-being."

Mr. Saul, the Canadian political philosopher, said that Bhutan's shift in language from "product" to "happiness" was a profound move in and of itself.

Mechanisms for achieving and tracking happiness can be devised, he said, but only if the goal is articulated clearly from the start.

"It's ideas which determine the directions in which civilizations go," Mr. Saul said. "If you don't get your ideas right, it doesn't matter what policies you try to put in place."

Still, Bhutan's model may not work for larger countries. And even in Bhutan, not everyone is happy. Members of the country's delegation admitted their experiment was very much a work in progress, and they acknowledged that poverty and alcoholism remained serious problems.

The pressures of modernization are also increasing. Bhutan linked itself to the global cultural pipelines of television and the Internet in 1999, and there have been increasing reports in its nascent media of violence and disaffection, particularly among young people.

Some attendees, while welcoming Bhutan's goal, gently criticized the Bhutanese officials for dealing with a Nepali-speaking minority mainly by driving tens of thousands of them out of the country in recent decades, saying that was not a way to foster happiness.

"Bhutan is not a pure Shangri-La, so idyllic and away from all those flaws and foibles," conceded Karma Pedey, a Bhutanese educator dressed in a short dragon-covered jacket and a floor-length rainbow-striped traditional skirt.

But, looking around a packed auditorium, she added: "At same time, I'm very, very happy we have made a global impact."

* Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

Link to Article Source

October 4, 2005

A New Measure of Well-Being From a Happy Little Kingdom

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

What is happiness? In the United States and in many other industrialized countries, it is often equated with money.

Economists measure consumer confidence on the assumption that the resulting figure says something about progress and public welfare. The gross domestic product, or G.D.P., is routinely used as shorthand for the well-being of a nation.

But the small Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan has been trying out a different idea.

In 1972, concerned about the problems afflicting other developing countries that focused only on economic growth, Bhutan's newly crowned leader, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, decided to make his nation's priority not its G.D.P. but its G.N.H., or gross national happiness.

Bhutan, the king said, needed to ensure that prosperity was shared across society and that it was balanced against preserving cultural traditions, protecting the environment and maintaining a responsive government. The king, now 49, has been instituting policies aimed at accomplishing these goals.

Now Bhutan's example, while still a work in progress, is serving as a catalyst for far broader discussions of national well-being.

Around the world, a growing number of economists, social scientists, corporate leaders and bureaucrats are trying to develop measurements that take into account not just the flow of money but also access to health care, free time with family, conservation of natural resources and other noneconomic factors.

The goal, according to many involved in this effort, is in part to return to a richer definition of the word happiness, more like what the signers of the Declaration of Independence had in mind when they included "the pursuit of happiness" as an inalienable right equal to liberty and life itself.

The founding fathers, said John Ralston Saul, a Canadian political philosopher, defined happiness as a balance of individual and community interests. "The Enlightenment theory of happiness was an expression of public good or the public welfare, of the contentment of the people," Mr. Saul said. And, he added, this could not be further from "the 20th-century idea that you should smile because you're at Disneyland."

Mr. Saul was one of about 400 people from more than a dozen countries who gathered recently to consider new ways to define and assess prosperity.

The meeting, held at St. Francis Xavier University in northern Nova Scotia, was a mix of soft ideals and hard-nosed number crunching. Many participants insisted that the focus on commerce and consumption that dominated the 20th century need not be the norm in the 21st century.

Among the attendees were three dozen representatives from Bhutan - teachers, monks, government officials and others - who came to promote what the Switzerland-size country has learned about building a fulfilled, contented society.

While household incomes in Bhutan remain among the world's lowest, life expectancy increased by 19 years from 1984 to 1998, jumping to 66 years. The country, which is preparing to shift to a constitution and an elected government, requires that at least 60 percent of its lands remain forested, welcomes a limited stream of wealthy tourists and exports hydropower to India.

"We have to think of human well-being in broader terms," said Lyonpo Jigmi Thinley, Bhutan's home minister and ex-prime minister. "Material well-being is only one component. That doesn't ensure that you're at peace with your environment and in harmony with each other."

It is a concept grounded in Buddhist doctrine, and even a decade ago it might have been dismissed by most economists and international policy experts as naïve idealism.

Indeed, America's brief flirtation with a similar concept, encapsulated in E. F. Schumacher's 1973 bestseller "Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered," ended abruptly with the huge and continuing burst of consumer-driven economic growth that exploded first in industrialized countries and has been spreading in fast-growing developing countries like China.

Yet many experts say it was this very explosion of affluence that eventually led social scientists to realize that economic growth is not always synonymous with progress.

In the early stages of a climb out of poverty, for a household or a country, incomes and contentment grow in lockstep. But various studies show that beyond certain thresholds, roughly as annual per capita income passes $10,000 or $20,000, happiness does not keep up.

And some countries, studies found, were happier than they should be. In the World Values Survey, a project under way since 1995, Ronald Inglehart, a political scientist at the University of Michigan, found that Latin American countries, for example, registered far more subjective happiness than their economic status would suggest.

In contrast, countries that had experienced communist rule were unhappier than noncommunist countries with similar household incomes - even long after communism had collapsed.

"Some types of societies clearly do a much better job of enhancing their people's sense of happiness and well-being than other ones even apart from the somewhat obvious fact that it's better to be rich than to be poor," Dr. Inglehart said.

Even more striking, beyond a certain threshold of wealth people appear to redefine happiness, studies suggest, focusing on their relative position in society instead of their material status.

Nothing defines this shift better than a 1998 survey of 257 students, faculty and staff members at the Harvard School of Public Health.

In the study, the researchers, Sara J. Solnick and David Hemenway, gave the subjects a choice of earning $50,000 a year in a world where the average salary was $25,000 or $100,000 a year where the average was $200,000.

About 50 percent of the participants, the researchers found, chose the first option, preferring to be half as prosperous but richer than their neighbors.

Such findings have contributed to the new effort to broaden the way countries and individuals gauge the quality of life - the subject of the Nova Scotia conference.

But researchers have been hard pressed to develop measuring techniques that can capture this broader concept of well-being.

One approach is to study how individuals perceive the daily flow of their lives, having them keep diary-like charts reflecting how various activities, from paying bills to playing softball, make them feel.

A research team at Princeton is working with the Bureau of Labor Statistics to incorporate this kind of charting into its new "time use" survey, which began last year and is given to 4,000 Americans each month.

"The idea is to start with life as we experience it and then try to understand what helps people feel fulfilled and create conditions that generate that," said Dr. Alan B. Krueger, a Princeton economist working on the survey.

For example, he said, subjecting students to more testing in order to make them more competitive may equip them to succeed in the American quest for ever more income. But that benefit would have to be balanced against the problems that come with the increased stress imposed by additional testing.

"We should not be hoping to construct a utopia," Professor Krueger said. "What we should be talking about is piecemeal movement in the direction of things that make for a better life."

Another strategy is to track trends that can affect a community's well-being by mining existing statistics from censuses, surveys and government agencies that track health, the environment, the economy and other societal barometers.

The resulting scores can be charted in parallel to see how various indicators either complement or impede each other.

In March, Britain said it would begin developing such an "index of well-being," taking into account not only income but mental illness, civility, access to parks and crime rates.

In June, British officials released their first effort along those lines, a summary of "sustainable development indicators" intended to be a snapshot of social and environmental indicators like crime, traffic, pollution and recycling levels.

"What we do in one area of our lives can have an impact on many others, so joined-up thinking and action across central and local government is crucial," said Elliot Morley, Britain's environment minister.

In Canada, Hans Messinger, the director of industry measures and analysis for Statistics Canada, has been working informally with about 20 other economists and social scientists to develop that country's first national index of well-being.

Mr. Messinger is the person who, every month, takes the pulse of his country's economy, sifting streams of data about cash flow to generate the figure called gross domestic product. But for nearly a decade, he has been searching for a better way of measuring the quality of life.

"A sound economy is not an end to itself, but should serve a purpose, to improve society," Mr. Messinger said.

The new well-being index, Mr. Messinger said, will never replace the G.D.P. For one thing, economic activity, affected by weather, labor strikes and other factors, changes far more rapidly than other indicators of happiness.

But understanding what fosters well-being, he said, can help policy makers decide how to shape legislation or regulations.

Later this year, the Canadian group plans to release a first attempt at an index - an assessment of community health, living standards and people's division of time among work, family, voluntarism and other activities. Over the next several years, the team plans to integrate those findings with measurements of education, environmental quality, "community vitality" and the responsiveness of government. Similar initiatives are under way in Australia and New Zealand.

Ronald Colman, a political scientist and the research director for Canada's well-being index, said one challenge was to decide how much weight to give different indicators.

For example, Dr. Colman said, the amount of time devoted to volunteer activities in Canada has dropped more than 12 percent in the last decade.

"That's a real decline in community well-being, but that loss counts for nothing in our current measure of progress," he said.

But shifts in volunteer activity also cannot be easily assessed against cash-based activities, he said.

"Money has nothing to do with why volunteers do what they do," Dr. Colman said. "So how, in a way that's transparent and methodologically decent, do you come up with composite numbers that are meaningful?"

In the end, Canada's index could eventually take the form of a report card rather than a single G.D.P.-like number.

In the United States there have been a few experiments, like the Princeton plan to add a happiness component to labor surveys. But the focus remains on economics. The Census Bureau, for instance, still concentrates on collecting information about people's financial circumstances and possessions, not their perceptions or feelings, said Kurt J. Bauman, a demographer there.

But he added that there was growing interest in moving away from simply tracking indicators of poverty, for example, to looking more comprehensively at social conditions.

"Measuring whether poverty is going up or down is different than measuring changes in the ability of a family to feed itself," he said. "There definitely is a growing perception out there that if you focus too narrowly, you're missing a lot of the picture."

That shift was evident at the conference on Bhutan, organized by Dr. Colman, who is from Nova Scotia. Participants focused on an array of approaches to the happiness puzzle, from practical to radical.

John de Graaf, a Seattle filmmaker and campaigner trying to cut the amount of time people devote to work, wore a T-shirt that said, "Medieval peasants worked less than you do."

In an open discussion, Marc van Bogaert from Belgium described his path to happiness: "I want to live in a world without money."

Al Chaddock, a painter from Nova Scotia, immediately offered a suggestion: "Become an artist."

Other attendees insisted that old-fashioned capitalism could persist even with a shift to goals broader than just making money.

Ray C. Anderson, the founder of Interface Inc., an Atlanta-based carpet company with nearly $1 billion in annual sales, described his company's 11-year-old program to cut pollution and switch to renewable materials.

Mr. Anderson said he was "a radical industrialist, but as competitive as anyone you know and as profit-minded."

Some experts who attended the weeklong conference questioned whether national well-being could really be defined. Just the act of trying to quantify happiness could threaten it, said Frank Bracho, a Venezuelan economist and former ambassador to India. After all, he said, "The most important things in life are not prone to measurement - like love."

But Mr. Messinger argued that the weaknesses of the established model, dominated by economics, demanded the effort.

Other economists pointed out that happiness itself can be illusory.

"Even in a very miserable condition you can be very happy if you are grateful for small mercies," said Siddiqur Osmani, a professor of applied economics from the University of Ulster in Ireland. "If someone is starving and hungry and given two scraps of food a day, he can be very happy."

Bhutanese officials at the meeting described a variety of initiatives aimed at creating the conditions that are most likely to improve the quality of life in the most equitable way.

Bhutan, which had no public education system in 1960, now has schools at all levels around the country and rotates teachers from urban to rural regions to be sure there is equal access to the best teachers, officials said.

Another goal, they said, is to sustain traditions while advancing. People entering hospitals with nonacute health problems can choose Western or traditional medicine.

The more that various effects of a policy are considered, and not simply the economic return, the more likely a country is to achieve a good balance, said Sangay Wangchuk, the head of Bhutan's national parks agency, citing agricultural policies as an example.

Bhutan's effort, in part, is aimed at avoiding the pattern seen in the study at Harvard, in which relative wealth becomes more important than the quality of life.

"The goal of life should not be limited to production, consumption, more production and more consumption," said Thakur S. Powdyel, a senior official in the Bhutanese Ministry of Education. "There is no necessary relationship between the level of possession and the level of well-being."

Mr. Saul, the Canadian political philosopher, said that Bhutan's shift in language from "product" to "happiness" was a profound move in and of itself.

Mechanisms for achieving and tracking happiness can be devised, he said, but only if the goal is articulated clearly from the start.

"It's ideas which determine the directions in which civilizations go," Mr. Saul said. "If you don't get your ideas right, it doesn't matter what policies you try to put in place."

Still, Bhutan's model may not work for larger countries. And even in Bhutan, not everyone is happy. Members of the country's delegation admitted their experiment was very much a work in progress, and they acknowledged that poverty and alcoholism remained serious problems.

The pressures of modernization are also increasing. Bhutan linked itself to the global cultural pipelines of television and the Internet in 1999, and there have been increasing reports in its nascent media of violence and disaffection, particularly among young people.

Some attendees, while welcoming Bhutan's goal, gently criticized the Bhutanese officials for dealing with a Nepali-speaking minority mainly by driving tens of thousands of them out of the country in recent decades, saying that was not a way to foster happiness.

"Bhutan is not a pure Shangri-La, so idyllic and away from all those flaws and foibles," conceded Karma Pedey, a Bhutanese educator dressed in a short dragon-covered jacket and a floor-length rainbow-striped traditional skirt.

But, looking around a packed auditorium, she added: "At same time, I'm very, very happy we have made a global impact."

* Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

Link to Article Source